A brief history of

Mosasaurus hoffmanni

by Faujas Saint-Fond

Published in the 7th year of the Republic, 1799

Copyright © 2004-2010 by Mike Everhart

Translated from the French by Jean-Michel Benoit

Last revised 05/07/2010

|

A brief history of Mosasaurus hoffmanni by Faujas Saint-Fond Published in the 7th year of the Republic, 1799

Copyright © 2004-2010 by Mike EverhartTranslated from the French by Jean-Michel Benoit Last revised 05/07/2010 |

Wherein Faujas Saint Fond describes the discovery of the skull of a crocodile (the type specimen of (Mosasaurus hoffmanni) from deep within one of the underground limestone quarries of Maastricht and some of the events which followed. (Click here for the map (plate II) mentioned by St. Fond, Note that north is to the right and the town of Maastricht is off the right edge. The location of the limestone quarry and Fort Pierre are shown in the red blocks). Jean-Michel Benoit generously translated the text for me while admitting that "I've had some troubles with it because it's written in old French (not as old as Ye Olde Middle Age François, but still...) So, when I had doubts, and believe me, this man had a very peculiar way of writing and of the use of commas, points, and the like..."

I've added my interpretation to portions of Jean-Michel's translation and apologize if I've mis-construed anything that he had done. In any case, so far as I am aware, this is the only English translation of this publication, and it is much more complete than the version published by Joseph Leidy (1865) and re-published by Williston (1898, 1914) and others. It is readily apparent that Saint Fond was trying to justify the removal of the fossil by the French Army. However, Eric Mulder (2003; pers. comm. 2003 and 2004), indicated that Dr. Hoffmann never actually owned the specimen, and the story of Canon Godding taking it from him was just that, a story. While many of the details are lost in history, it is apparent that Dr. Hoffman was instrumental in bringing this important specimen to the attention of the scientists of the day, including Camper and Cuvier, and deserves the recognition that he received in having it named after him.

Saint Fond wa among the first to publish a description of the skull of Mosasaurus hoffmanni, including so far as I am aware, the first mention of scavenging of a mosasaur by marine animals (sharks) on p. 64, measurements of the specimen and number of teeth in the jaws, the presence of "secondary teeth" (replacement teeth) on page 65, and the presence of teeth on the pterygoid bones (p. 66 - he credits the work of Camper here).

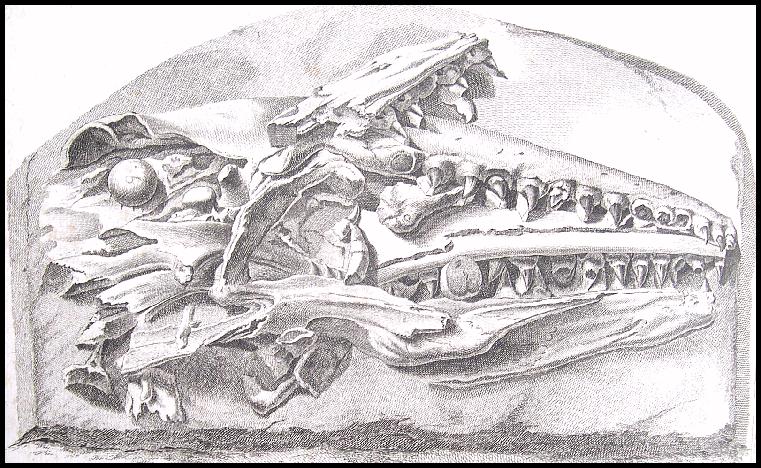

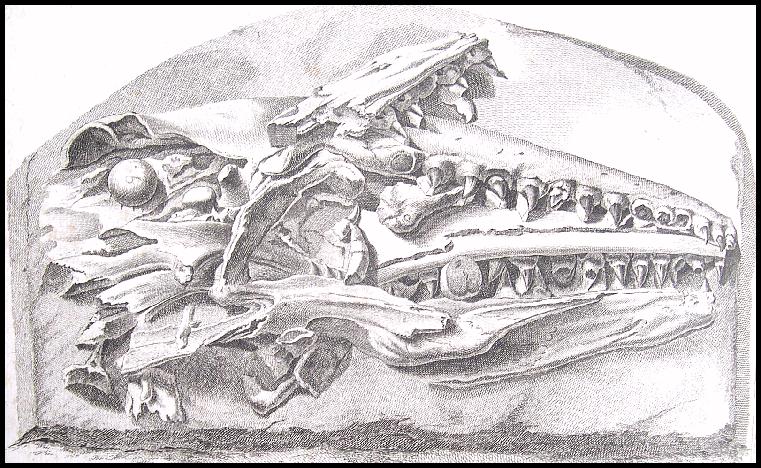

OF MOUNT ST. PIERRE 59

HEAD OF THE CROCODILE

PLATE IV. [Above] _____________________________

It was in one of the galleries of the mountain Saint-Pierre near Maestricht, at a distance of five hundred paces approximately from the main entry, plate II, that workmen busied in drawing out stones, in 1770, recognized from six feet above in the layer in which they were digging, the remainder of the head of a large animal embedded in the solid mass of the stone; that appeared very remarkable to them. They suspended their work to tell of their discovery to Dr. Hoffmann, who for a long time had built a collection of fossils from the mountain. They were very careful in advising him every time an important enough object was found. This naturalist, legitimately jealous of possessing the best preserved remains, generously rewarded the workers who told him about such remains without having to disengage them himself. This object, the most considerable found as of |

60 NATURAL HISTORY yet, gave great pleasure to the good Hoffmann. All possible precautions were taken to obtain this head intact. Because the stone was very soft, one managed to get it with lots of care and by cutting around the block from very far, so as to obtain a solid mass in width and volume. Nothing equalled the intense pleasure and ecstasy that this naturalist felt, working with his hands for days in disengaging this block, diminishing it, shaping it, and through lots of care and assistance, getting it out of the mine, and transporting it to his home in triumph. But this great conquest in natural history, which gave him so much satisfaction, was soon to be the object of a great sorrow. One of the canons of the town owned the land soil under which the stone mine was located and into which the crocodile had been found. This ecclesiastic, despite his lack of interest in natural history, imagined, based on a feudal law, to claim the object which certainly didn’t belong to him on any basis, and couldn’t be assimilated to a treasure, or a gold or silver mine. However, the renown of this beautiful object gave it a great value; and this word seduced the recipient. Hoffmann defended his cause with courage; the affair became serious; the judges intervened, the Canon won, and the poor Hoffmann lost his crocodile and had to pay. One can judge of his despair and the disgust he felt for such researches that gave him so much happiness before. Many of the beautiful fossils from Maestricht Mountain, displayed in the cabinets of Holland or Germany are his due; and from this point of view, natural history has obligations towards him. |

OF MOUNT ST. PIERRE 61 Canon Godin, leaving the remorse to the judges for their bad decision, became the pleased and quiet possessor of an object that was unique in its kind. He placed it like a relic in a large glazed mounting, and moved it to a field house that he owned at the base of mountain St. Pierre. Curious people and strangers were admitted for the viewing. Apart from his litigious mind, the canon was a rather jovial fellow, and the crocodile was the witness of many a libation made in its honour. Each time it was visited, and on this point, the canon was liberal, he provided his best Rhine wine. Justice, although late, came at last with time. The crocodile’s location was to change place once more and soon after to change masters. The Army of the French Republic having, in 1795, pushed back the Austrians and set siege at Maestricht and bombarded Fort St. Pierre. The Canon’s country house was located near the Fort and the general, who was informed that the crocodile’s head was there, gave specific commands to the artillery to spare this house. But the Canon, no less far-sighted, and ignoring the protection given by the French artillery to his house, had the crocodile moved during the night, and placed in a secure location in town. Everything went well until the town, unable to defend itself, had to capitulate. But when the French Army took possession of the town, the French People’s Representative Freicine offered to anyone who would discover the crocodile’s location, a reward of six hundreds bottles of wine, as long as the piece would be protected from any damage and arrived in good state. This promise had its effects. The next day, twelve

|

62 NATURAL HISTORY grenadiers brought the crocodile to the Representative’s house in triumph. Not only was the reward granted, but the decision was more fair towards the Canon than he had been towards Hoffmann. He was first exempted from war contribution, whereas his fellow canons had to pay it, and it was then agreed that the value of this nice specimen, which was to be sent to Paris, would be estimated there by scientists, and that amount would be paid to its owner. This act of generosity, or rather justice, should have been directed towards poor Hoffmann, but by then this scientist was dead, and his family no longer lived in Maestricht. This accurate tale should not be regarded as a foreign matter to natural history. Since the Maestricht crocodile is now in Paris Museum, the circumstances which brought it there deserved to be known, especially when one considers that this conquest, as the result of the valour of the French troops, proves that these excellent soldiers have always known how to appreciate and respect the monuments and all objects related to sciences. They have proven a thousand times since then that the same consideration for the “beaux-arts(?)” always moved them; a circumstance forever memorable in such an awful war. Description of the animal’s head The block of stone in which the bones of the head are encased is four feet wide, two feet six inches high, and eight inches thick. Originally this stone was much larger, weighing almost six hundred pounds, but when it had to be transported to Paris, its volume was diminished as much as possible, without |

OF MOUNT ST. PIERRE 63 weakening its solidity. They were careful to facilitate its transportation and protect it from any accident by encasing it in a strong wooden frame, secured by iron bolts, which could be tightened as necessary to maintain and lock the stone at every point. Everything succeeded, and allowed this beautiful piece to reach Paris in the best condition, where everyone can see it in the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle. The maxillary bones and others which are in part exposed in this stone are rather fossilized than petrified: They have similarities, concerning their state, that is their colour, their hardness and their physiology, if it is correct to employ such a expression here, with fossil bones found in the quarries of Montmartre, near Paris. However, those from Maestricht have a much tighter structure, more compact, their colour is a yellowish brown, darker but at the same time more polished. The bony root of the teeth is heavy, and has a petrified look. The enamel has kept part of its polish on the external side, but the surface of the tooth is brittle, although very fine and compact. Time, without having altered it greatly, has nevertheless weakened it so as to be easily broken. On the whole, appearance of this head could make one believe, at first sight, that the maxillary bones are nearly in their natural position; but a more thorough examination definitely indicates that the head has suffered a great disturbance in its structure; i.e. most of the bones have been displaced. This is not surprising, because the animal being dead naturally or accidentally, and laying at the bottom of the sea, its flesh must have been prey to voracious marine animals, which would have |

| 64

NATURAL HISTORY removed its muscles, pulling on their attachments in every way, so as to separate several of the body parts. Sands would have then settled and accumulated in great numbers over the united or scattered remains of this large animal. We would then expect similar results to the actual state of the fossil and the position in which these bones were in the middle of the hardened sands which compose the Mount St. Pierre. It is also possible, and this hypothesis is also possible, that the dead body of the animal whom we talk here, after having lost its flesh, and having floated some time in the waters, had been carried by a swift stream to the quick sands along with turtle debris and that of other animals. These can be found nearby and are mixed with the shells of numerous species, which couldn’t have lived and propagated in such a confusion. The sand deposits are of such a great thickness, and were confusedly accumulated through the effect of a great displacement. 1°. Considered from an anterior view the jaw bones of this head, either on the original specimen, or on the picture, which is perfectly accurate, the one on top is a broken part of a maxillary bone, very well preserved in what remains, measuring one foot, four inches, six lines [Translators note: An old French measure representing the twelfth part of an inch, roughly 2.25 mm] in length, and four inches in width. It bears four well preserved large teeth, from the root of which emerge a very peculiar small secondary tooth, of which it will be discussed in time. This portion of jaw lacks three other teeth for which alveoli are visible. 2°. Immediately below this fractured maxillary bone, diagonally laid on the stone, one can see a second upper jaw bone disposed longitudinally and |

OF MOUNT ST. PIERRE 65 seemingly in its natural place, entire and perfectly preserved, excepting some teeth that have been broken out. This lower maxillary bone is three feet, nine inches long; its width in the middle is four inches, six lines. There are fourteen teeth. The enamel of the largest is two inches three lines long. Their circumference near the root is two inches seven lines. The length of the small auxiliary teeth situated at the root is one inch six lines. All these latter ones are not readily visible, and only show varying portions of the tip; but I have found the dimensions within one the secondary teeth, which is entirely exposed, complete with a root which is separated from the alveoli. One will find this tooth figured in one of the plates. One can see distinctly along the lower part of the maxillary bone, eleven oblong shaped small openings used for the nerve insertion, disposed on the same line; whereas towards the extremity of the animal’s muzzle side bone, smaller insertions, closer and in a greater number, spread all over the surface of this part of the bone on a space of about ten inches in length. 3°. Immediately below the maxillary bone which has just been mentioned, there is a second bone, of about the same size and length; but less well preserved: there are thirteen apparent teeth; others are covered |

66 NATURAL HISTORY and hidden by bone fragments. Beside it, there are two separate teeth lying out of their alveoli, with corresponding crowns. 4°. A fourth maxillary bone, which seems to complement the jaw, is placed longitudinally below the others; but slightly deeper, in a reversed sense and in opposition with the rest of the others: it shows seven teeth. The others are hidden. 5°. A curved bone, touching the one in n°4, and which seems to form a continuation of the maxillary bone in the animal’s palate, bears several much smaller teeth: this has led Camper to say that the animal must have had several teeth in the palate: four of them are visible; it is said that there had been up to six or seven of them. The enamel of these small teeth is the same shade of color as the larger ones, but they are simpler, i.e. they lack secondary teeth at their roots, whereas the main ones have them. From what we just said, it appears that the bones composing the jaws of this peculiar animal are to be found, for the most part, in the same block. They are not in their natural position, to be sure, but have suffered displacements which are necessarily due to the forces which buried the remains of this head in the depth of the sands, at the time of a great flood. However, as one of these maxillaries is perfectly preserved, and its shape well characterized, it is possible, as we will show it later, to obtain exact data concerning the size of this head and that of the animal; but we will reserve this discussion for the eighth and ninth deliveries [Translators note: An old French term [livraison] which means delivering the writings for publication as soon as they are |

OF MOUNT ST. PIERRE 67 written), where it will be examined whether this head belonged to an unknown cetacean or to a new species of crocodile, different from the Nile and the Ganges crocodiles. Some vertebrae are mixed randomly with other bone fragments within the block of which we just spoke and over the jaws of the animal from Maestricht: one can also distinguish two echinites [Sea urchins?] which adhere to it, one seen on top, the other below. It will be made mentions of this urchin species within the description of fossil and petrified shells found in Mount St. Pierre.

|

Credits: I wish to thank the Director and staff of the Natural History Museum of Maastricht for access to and permission to photograph their copy of the "Historie Naturelle de la Montage de Saint-Pierre de Maestricht" by Faujas Saint Fond. I am also grateful to Jean-Michel Benoit for his translation of the chapter regarding the "Head of the Crocodile" and his assistance in providing translations of many Oceans of Kansas webpages into French.