|

Finding My First Mosasaur in South

Dakota

August, 1998

With the Field School from The South Dakota School of

Mines and Technology in the Pierre Shale

Copyright © 1998-2009 Mike Everhart

Last Updated 01/30/2009

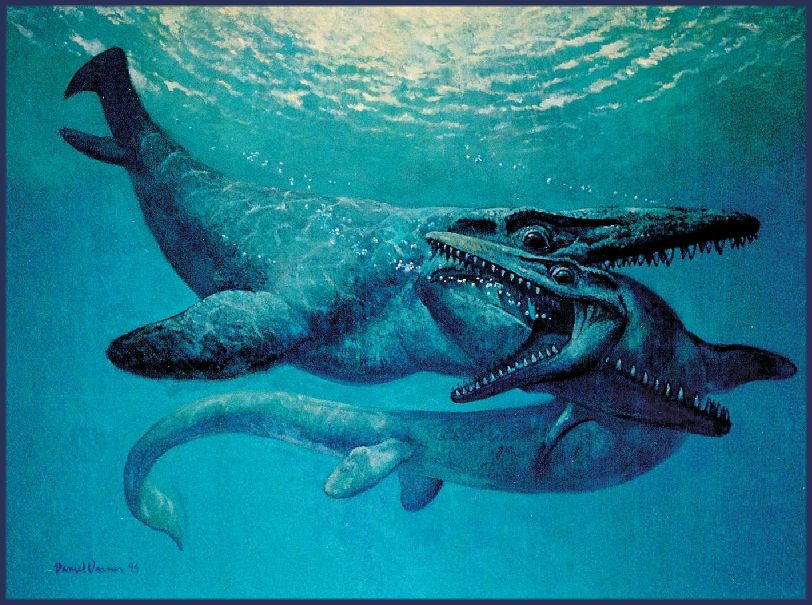

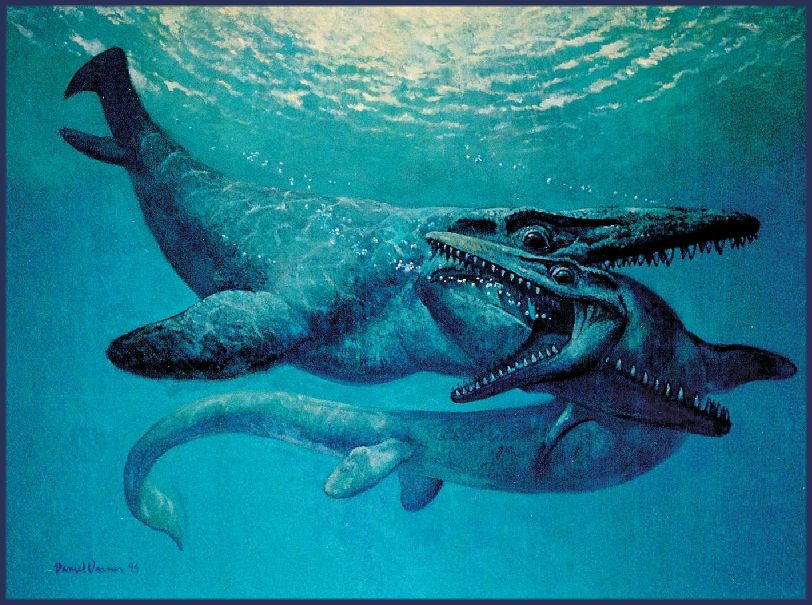

Copyright © Dan Varner; used with permission of Dan Varner |

As sort of a mini-vacation during the summer of 1998, we decided to visit the Field School

sponsored by the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology and the New Jersey State Museum. The field portion

of the school involves an ongoing paleontological survey of Indian lands along the east

bank of the Missouri River near Fort Thompson, S.D. Several of our friends (Jim Martin,

David Parris, Gorden Bell, and Barbara Grandstaff) run the school and provide instruction

/ direction for the students. The two week school sets up tents in a campground along the

Missouri River near Chamberlain, South

Dakota. Students can take the course for credit and this year there were more than 30

students enrolled.

We arrived on Wednesday afternoon, August 6, and found that everything was

still pretty damp from a heavy rain they'd had two days earlier. In fact, they hadn't been

able to get into one of their sites on Tuesday, so one group had gone across the river and

started prospecting in the upper Smoky Hill chalk (just below the Pierre contact). As luck

would have it, they found a lot of little late Cretaceous material, including a large but

very scattered Xiphactinus audax, and...get this.... a

complete buffalo skull that had washed down into a chalk gully and been re-buried hundreds

or thousands of years ago. Turned out to be a great specimen …. but it took them

three days to get it exposed and jacketed so that it could be safely removed.

|

A view of the rolling terrain covering the Pierre Shale, looking

west towards the Missouri River, near Fort Thompson, S.D. The mosasaur locality is on the

far side of the darker colored hill in the center of the picture. (Click to enlarge picture). |

We headed out to the field early on Thursday morning. Our half of the group had

been working up near Fort Thompson in the DeGrey member of the Pierre Shale along the east

bank of the Missouri River and hadn't had too much luck the first two days. Gorden Bell

was finishing the excavation of a scrappy mosasaur specimen that he'd found a couple of

years back. The find consisted mostly of vertebrae, but on Tuesday, Gorden had found the

upper end of a front limb bone, the humerus. It was totally three dimensional, not at all

like the flattened remains that we find in the chalk. It gave me a new appreciation for

how massive these mosasaurs were!

Most of the students and staff started scouting around while Gorden and a few

of us got dirty finishing the recovery of the mosasaur. I pitched in and helped Gorden

undercut the specimen so that it was sitting on a pedestal of shale. Then we put several

layers of plaster and burlap to make a field jacket on it. Once the plaster had dried, we

undercut it some more, and then….. drum roll…. moment of truth…. we turned

it over. As planned, everything stayed in place inside the jacket, but there is always a

concern that the shale supporting the specimen will fall out when the jacket is turned

over. Several inches of shale were then removed to lighten the jacket before the opening

was sealed over with plaster and burlap.

After we rolled the specimen, I took off and walked a few miles, over and

around the hills, down to the river and back....and didn't find a thing! My previous

experience of finding vertebrate material in the Pierre Shale has never been good and it

wasn't improving! About noon, I made it all the way back up the hill and ate lunch while I

tried to replenish a gallon or so of lost fluids. Even though it wasn't really hot yet, it

still was warm enough to dehydrate you fairly quickly if you were moving around.

After lunch, I noticed Gorden and one of the SDSMT volunteers working on a

shale outcrop. They stayed in the same little area for several minutes and I figured that

they had found something. When I joined them, Gorden was trying to figure out the

stratigraphy of the Pierre Shale in the vicinity of a really fragmented mosasaur skull.

Another group joined us and we showed them what to were looking for. Within a half hour or

so, we had picked up several small bags of bone fragments, including identifiable teeth.

Gorden kept digging around until he found the bentonite layers that he was looking for, so

he was happy. The Pierre Shale in this area had not been systematically collected before,

so Gorden and the others were trying to get as much data as possible with each specimen to

better define the occurrences of the various species.

When we had finished collecting dozens of bone bits, Gorden asked if anyone had

checked uplands to the east of our location. He said that if we hadn't yet, we were going

to have to come back to this locality and do it the next day. There was a lot of shale

exposed above us, so it seemed like a good place for me to wander around. I grabbed my

gear and began walking up the hillside. Within ten minutes, I had found myself a mosasaur.

(You can look at a drawing from my field notes to get a

better idea of what is shown in the pictures that follow: "V" is for vertebra,

"Q" is for quadrate)

|

This picture shows the remains of the mosasaur as I found it. Most

of the bones were enclosed in an "ironstone" concretion that had fragmented and

was sliding down piece by piece into the gully as the weathered shale was eroded from

under it. It became quickly evident to me that part of the problem with finding vertebrate

material in the shale is just being able to see them! A few vertebrae are barely

recognizable at the far right hand side of the photo. The reversed "C" shaped

outline of one of the quadrates is also faintly visible

under the end of the tape measure at the left hand side of the picture. In mosasaurs, the

quadrate provides the hinge point to attach the lower jaw to the skull, and supports the

tympanic membrane of the outer ear. It is also a diagnostic feature in determining the

species in mosasaurs. |

I had walked over a grassy area between two gullies on the way to the side of

the hill and practically stepped on the bones as I came down the steep slope. It was dumb

luck finding the bones in the first place, but in paleontology, dumb luck is better than

no luck at all. The remains were from a big animal, probably a Mosasaurus

conodon. They were eroding out the side of gully in a fragmented,

"ironstone" concretion. After looking it over closely one more time to make sure

I wasn't just wishfully hoping to find something, I walked back down the hill and asked

Gorden to come have a look. Gorden quickly picked out various elements of a mosasaur skull

in the concretion and it looked like it was going to be the find of the day, and maybe the

week. It certainly made my day.

|

This photo shows a closer view of the fragment containing the

mosasaur's quadrate (between and below the 2 and 6 inch

marks on the tape measure). There were also several pieces of jaw elements, including

teeth (which are not visible in the picture) and vertebrae mixed together in this piece.

Again, the bones were not readily visible in the field and are even less so in this

picture. |

We brought the students up the hill at the same time to show them what mosasaur

material looked like in the shale. They all had a real hard time seeing the dark brown

bones in the reddish brown matrix of the concretion. I could sympathize with their

frustration since it had taken me the equivalent of almost a week of prospecting in the

field over the past several years to find something major! By that time, it was too late

in the day to do anything except take a few pictures before we rounded everyone up and

headed back to the campsite.

|

This photo shows an overall view of the specimen as it was exposed

on Friday. All of the bones were within a 4 foot by 4 foot square. As we dug back into the

side of the gully, we found that the bones were no longer enclosed in the concretion.

Digging at the site the following week found additional skull material and vertebrae. |

The next day (Friday) we returned to the same area and two of us exposed the

specimen. There wasn't much visible near the surface (mostly bones of the skull and

probably 20 vertebrae). The specimen went into the steep side wall of the gully and would

take major excavating if it was complete. It took us most of the day to expose the most

accessible part of the remains. By mid-afternoon, we had both of the quadrates and a lot of jaw material, plus some bones that

looked like they came from the back of the skull. It was found within five feet of the top

of the DeGrey member of the Pierre shale, so it also produced stratigraphic information

that was useful to the work being done by the SDSMT.

|

My final view of the specimen

before we began jacketing the remains for the long trip up the hill and back to the SDSMT

Museum of Natural History. Judging from the dis-articulation of the skull and vertebral

column, it appears the mosasaur's bones had been moved around by tidal currents before

being buried. The fact that the bones were piled together may have contributed to the

formation of the concretion through some chemical reaction within the bottom mud. While

the concretion containing the bones had fragmented by the time the specimen was found, the

bones were not damaged and the pieces still fit together well. |

After we had it uncovered as far as we were going to go, I spent a few minutes

and made a crude sketch of the remains in my field notes.

This would stay with the materials we removed and hopefully aid the technicians during the

preparation of the remains. We spent a couple of hours late in the day jacketing the loose

fragments that had been exposed at the edge of the gully. I wanted to at least be part of

removing some of the specimen, since I wasn't going to be there for the rest of the dig

(and probably won't ever see the remains again). It was a long hot day in the gully, but a

lot of fun (I guess paleontologists have a warped sense of humor concerning

"fun"). Later, I heard from Gorden Bell that further excavation of the site had

led to the discovery of most of the rest of the skull. My first discovery in the Pierre

Shale turned out to be a very good specimen after all.

See another SDSMT mosasaur dig in South Dakota here.

See a portion of the mosasaur collection at the Museum of

Geology, South Dakota School of Mines and Technology... HERE

BACK TO INDEX