|

PARTS IS PARTS AND PIECES IS PIECES

...........and there are lots of pieces of mosasaurs

Written and Illustrated by Mike Everhart; Copyright ©

1999-2009

Last updated 04/23/2010

NEW - 05/14/2003 - Translated into

French by Jean-Michel Benoit

Image adapted from a painting by

Vladimir Krb, courtesy of and copyright © by the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology.

Click here to see the larger version (60 kb). |

To be truthful, I never intended to do much with these left-overs from a Late

Cretaceous marine predator's lunch. I had realized that they were probably the remains

from some sort of feeding activity, but that is what one would expect in an depositional

environment where big animals had sharp teeth and fed on other big animals. Taken

individually, the specimens shown below are just collections of associated mosasaur bones,

most of which appear to be badly weathered and generally unidentifiable. Over the last

several months, however, it has become apparent that these remains probably share a common

origin.

The shared element among all of these specimens is that they are evidence of

attacks and/or feeding by a species of giant sharks during the Late Cretaceous (Latest

Coniacian time, approximately 85 million years ago). The shark has been identified from

the teeth that it left embedded in some of the bones as Cretoxyrhina mantelli.

“Mantelli’s Cretaceous Shark” was about the same size as a modern Great

White shark but was not closely related. It is also what I have come to call the

“Ginsu Shark” because of its rather decisive bite.

For those of you who have not been subjected to American television commercials

over the last 20 or 30 years, ‘Ginsu Knives’® were and are still being

advertised as very sharp and strong, along with the catchy phase, “It slices and

dices”. It seemed appropriate to apply that name to an eighteen foot shark with jaws

full of sharp, blade-like teeth that seems to have ‘sliced and diced’ its meals.

It has been estimated that the amount of biting force that a large shark can exert on its

prey easily exceeds 10 tons per inch.

Kenshu Shimada and I first reported on a shark bitten

mosasaur specimen in 1995. That material later was donated to the Sternberg Museum at

Fort Hays State University and will hopefully be part of the new exhibits when the museum

opens in its new quarters in March, 1999. The specimen consisted of a 12 inch section of 5

articulated vertebrae from the lower back of a large (18 foot) mosasaur. The vertebrae at

each end had had been sheered completely through and there were several Cretoxyrhina

teeth embedded in the bone. The bones appeared to have been partially dissolved by acid,

suggesting that the shark had swallowed this large hunk of a mosasaur and then later

regurgitated the indigestible bones. In this case, and others, the pieces were apparently

held together by enough of the remaining skin, muscle or ligaments to reach the sea

bottom. Only those portions of the mosasaur's bones that were exposed during digestion

were damaged by the sharks stomach acids.

This discovery generated enough interest that Paleoworld (Wall to Wall

Productions, LTD) became interested and filmed the specimen in 1997 for an upcoming

episode called "Prehistoric Sharks". Kenshu Shimada

also published more information about that specimen in his paper “Paleoecological

Relationships of the Late Cretaceous Lamniform Shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli

(Agassiz)", Journal of Paleontology, 71(5), 1997, pp. 926-933.

While working with this specimen, I recalled that we had other ‘parts and

pieces’ in our collection that also showed evidence of shark bite, digestion, and/or

traumatic injury. Two other specimens included embedded Cretoxyrhina teeth.

Fourteen specimens of probable shark related feeding activity have now been identified.

Apparently, Cretoxyrhina was not overly awed by the mosasaur's size and ferocity,

and was not particular as to what part of the mosasaur that it fed upon. For a brief

period in the Western Interior Sea, giant sharks were the top predators.

Also, you can check out Jim Bourdon's "EXTINCT ELASMOBRANCH Specimens and

Paleo-Faunas" site for lots of expert information about sharks and rays, as well

as links to current Shark Pages around the world.

I have recently added pictures of most of these specimens on the following

pages. While the photos are lacking somewhat in quality, they do adequately portray the

overall impact of this feeding activity. The numbers on the drawing below provide a

general idea of the locations of the recovered shark bite specimens.

Click on the thumbnail images below to see the larger pictures.

|

The lower jaws and premaxillary of a 36 inch Tylosaurus

sp. skull. (1) The bones from the large Tylosaur skull shown above have the tips of at

least three Cretoxyrhina teeth embedded in them; one each in the outside of the

left and right dentarys, and one in the premaxillary. This specimen consisted of the

skull, lower jaws and several upper limb bones. Since it was badly weathered before

discovery, much of the evidence of shark bites may have been lost. There are, however,

several tooth marks across the muzzle (premaxillary), and the most anterior bite may have

taken off a large chunk of the bone. The shark bites visible on the skull were not fatal

and it is possible that this mosasaur survived this encounter with the shark, and died

later of other causes. |

|

This picture of the premaxillary shows the location of bite marks

(white arrows. From the direction of the bite marks and the location of the embedded

tooth, it would appear that the shark bit from the right side of the mosasaur's head. This close up shows the location of the embedded tooth, and

a groove leading toward the embedded tooth, as well as damage done to the tip of the

premaxillary. It appears that the bite of the shark closed on the tip of the muzzle and

cut deeply enough into the bone to shear off the end of the mosasaur's snout. |

|

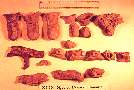

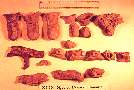

The remains of a shark bitten mosasaur skull and vertebrae. (2)

This mosasaur was not so ‘lucky’. The specimen consists of numerous, almost

completely digested skull fragments and several vertebrae. Since what’s left of the

remaining vertebrae do not appear to be cervicals, it appears that the shark took several

bites from different parts of the mosasaur and then regurgitated the indigestible pieces

all at the same time. Note the way that the mosasaur’s teeth have been dissolved away

from the jaw fragments and the remaining pterygoid. |

|

The severed and partially digested muzzle of a small mosasaur. (3)

This picture shows upper and lower views of a fragment from the anterior end (muzzle) of

the skull of a small mosasaur that met a rather quick end. The specimen consists of most

of the premaxillary bone, and the anterior ends of both maxillaries. The snout was

apparently severed from the rest of the skull by a shark bite across the nose that cut

completely through the bones. This piece was swallowed, partially digested (note missing

teeth) and regurgitated with enough flesh left on the bones to hold them together as they

fell to the sea bottom. There's a story to go along with

this picture. |

|

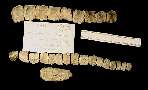

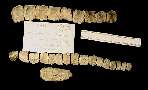

The last remains of five small mosasaurs. (3) These are the upper

and lower view of five premaxillae from several very small mosasaur skulls that have all

been partially digested. They were the only material that was found from each individual.

The premaxillary appears to be the most ‘survivable’ part of a juvenile

mosasaur’s skull because of the relative thickness of the bone. |

|

The neck of a very unlucky mosasaur. (4) These are cervical (neck)

vertebrae from a medium sized mosasaur that obviously lost its head and its body somewhere

along the way. Although highly eroded by acid, and with at least two of the vertebrae

appearing to have been severed by a strong bite, there is no evidence of embedded teeth in

this specimen. Interestingly, these vertebrae came from about the same stratigraphic level

as, and about a quarter mile removed from a headless / neck-less / limb-less / tail-less

series of shark scavenged mosasaur vertebrae. The odds against finding two parts of the

same shark scavenged animal would be astronomical at best, but I suppose that it is

possible. |

|

A big bite out of the middle of a large (6-7 meter) mosasaur. (5)

This once was a large piece of a large mosasaur (8-9 meter). These vertebrae probably came

from the lower back (abdominal). Unfortunately, there were no embedded teeth or teeth

marks remaining, but the several of the vertebrae show evidence of being damaged (severed)

by the shark's bite. |

|

Biting below the waist.....Ouch!.....I bet that hurt!! (6) This

specimen is all that remains of a portion of a mosasaur’s pelvic girdle that had been

almost completely digested while inside a shark’s stomach. The vertebrae are from the

hip region (pygals) or nearby caudals. There is almost no area of bone surface that has

not undergone severe acid attack. |

|

A bite sized piece from a mosasaur limb. (7) This is a single limb

bone (probably a humerus) that has been badly damaged by stomach acid. There is a readily

visible and quite deep cut mark from a blade-like tooth through part of the bone (arrow)

which was probably made when the shark severed the limb from the mosasaur. |

|

A twice bitten mosasaur tail. (8) The next specimen comes from the

south end of a north bound mosasaur and represents the vertebrae at the tip of a

mosasaur’s tail. In this case, the large lump is three fused vertebrae that were the

result of an infection from a much earlier bite that severed the tip of the tail. The

mosasaur apparently survived long enough for the wound to heal and then ended up as a

meal. Larry Martin and Bruce Rothschild reported on a larger but similar specimen of fused

mosasaur vertebrae several years ago. Click here for a

close up of the fused vertebrae. |

|

Nibbling at the tail.....several small bites from the same

mosasaur (9) These caudal vertebrae also ended up inside a shark as a meal. Based on the

fact that the several ends of the vertebrae were partially dissolved by acid, it appears

that the mosasaur’s tail was actually taken in several smaller bites. |

|

Another bite sized morsel of mosasaur tail. (10) This was my first

shark / mosasaur find for 1998......a short (bite-sized) series of four caudal partially

digested prior to fossilization. |

RECENT REFERENCES:

Shimada,

K. 2008. Ontogenetic parameters and life history strategies of the Late Cretaceous

lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli, based on vertebral growth increments. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 28(1):21-33.

OTHER WEB PAGES:

Kansas Sharks - Cretaceous shark remains, mostly

teeth, from Kansas

The discovery of a giant Ginsu Shark - The remains

of a 7 meter shark found in the Smoky Hill Chalk.

Cretoxyrhina mantelli -

The Ginsu Shark - The discovery of mosasaur remains scavenged by two species

of sharks.

Cretoxyrhina mantelli and Squalicorax

falcatus - Here are some pictures of the teeth of these sharks.

A Moment in Time - Another example of Cretoxyrhina

mantelli feeding on a mosasaur.

One Day in the Western Interior Sea..... Life could

be very short for the unwary.

One Day in the Life of a

Mosasaur - Being the top predator is a lot of hard work!

BACK TO INDEX