| 122

Kansas Academy of Science SOME ANIMALS

DISCOVERED IN THE FOSSIL BEDS OF KANSAS.

By CHARLES H.

STERNBERG, Lawrence. Kan.

F or many years past the writer of this paper has given his entire

time to the collection and preparation for exhibit of fossils from several Western states,

giving much time to the rich fields of western Kansas, so prolific in fine examples of

ancient vertebrate life. Some mention of some of the best finds made within the last few

years and where these have gone, many being lost forever for any Kansas museum, is worthy

of record.

A complete skeleton

of a new plesiosaur was found by the writer's son on the Hathaway ranch, on Beaver

creek, Logan county, and which is now in the museum of the University of Kansas, having

been mounted by the very competent preparator, Mr. H. T. Martin.

A nearly complete skeleton of Portheus colossus [sic], of Cope, collected

on Robinson's cattle ranch, in Logan county, within stone's throw of the stable, is now

mounted in the American Museum, at New York, and is said to be the best example of a

fossil fish in any museum in the world.

There have also been sent to this museum from the

Kansas fields eight other splendid specimens, including a very fine skull of the great

ram-nosed Tylosaurus and the skeleton of a smaller form of Portheus. This

has enabled that museum to restore and mount a nearly complete skeleton procured some

years ago from Mr. W. O. Bourne, of Scott City, Kan., in which the head was distorted.

This fine skull was found on Butte creek, 100 feet above where the writer had previously,

in 1881, found as good a one, which is now in the Museum of Comparative Zoology, at

Cambridge, Mass.

To Vassar College was sent a fine skeleton of Clidastes

and also one of Platecarpus, both from Logan county.

To the Carnegie Museum, at Pittsburg, Pa., much

material has been sent, including the most complete skeleton of Protostega

ever found in the Kansas chalk- beds. This great turtle measured ten feet between the

front paddles. There was also sent this museum a fine skeleton of the great predaceous

fish, Portheus colossus [sic].

To the British Museum has gone quite a collection,

including a nearly complete skeleton of the great broad-handed lizard, Platecarpus

coryphæus, a nearly complete skeleton of a Pteranodon,

with the best skull that the writer has ever collected. There was also

Geological Papers.

123

included a fine pair of fins with pectoral arches connecting them of the

well-armed snout-fish, Protosphyraena. Each fin,

enameled and sharp as a knife, with forty teeth; is three feet in length. What must have

been a strong and effective weapon of offense or defense is shown in a skull of this same

fish, with its long, bony rostrum, oval in section and terminating in a sharp point. In

addition to this dagger, fixed at the end of the head, the snout-fish possessed eight

sharp, lancet-shaped teeth that projected forward. When the sharp point of the rostrum was

driven into the victim's side these lancets widened the rent, till the animal's head could

be forced into the breach up to its eye-rims, while their forward slant enabled the head

to be quickly withdrawn for a fresh attack. Even the Kansas mosasaurs, who were no mean

fighters themselves, must have avoided this great fighter among fishes.

A nearly complete skeleton of this same lizard is

displayed in the museum of the University of Iowa. This was a large specimen, twenty-five

feet in length, with the bones well bedded in the natural chalk.

The finest saurian ever found on any of the writer's

expeditions came from the Mendenhall pasture, on Hackberry creek, in Gove county. The

specimen was complete, except for the upper portion of the head. The massive jaws are

present, and the bones generally are beautifully preserved, and so little distorted by

pressure that the specimen can be given an open mount. Even the breast-bone and the

cartilaginous ribs are present, this being the first time that these bones have been found

in the remains of this animal. This fine specimen of Platecarpus coryphæus was

sent to the Roemer Museum, at Hildersheim, near Hanover, Germany.

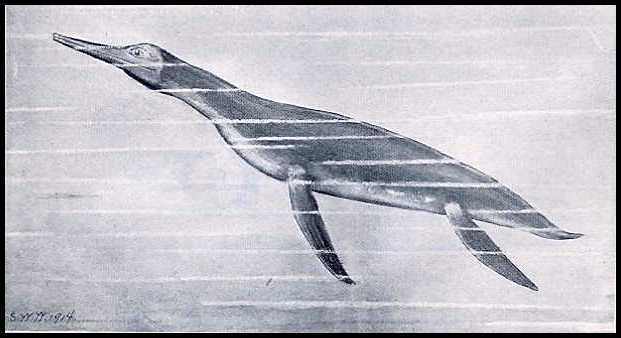

The first restoration of a Platecarpus skeleton

ever attempted in the United States, the material being from Kansas beds, was sent to

Doctor Krantz, a dealer of Bonn, Germany. With this went the material for an open mount of

the Kansas rhinoceros, Teleoceras fossiger, from the Sternberg quarry, near Long

Island, Kan.

There has been sent to the Munich Museum a complete

set of lower jaws and also a number of inferior tusks of Mastodon productus (

Cope).

The same museum possesses an unusual specimen of an

ancient shark, Oxyrhina mantelli, found on Hackberry

creek, Gove county, Kansas, in 1890. The remarkable thing about this specimen is that the

vertebral column, though of cartilaginous material, was almost complete, and that the

large number of 250 teeth were in position. When Chas. R. Eastman, of Harvard, described

this

124 Kansas Academy of Science.

specimen, it proved so complete as to destroy nearly thirty synonyms used to

name the animal, and derived from many teeth found at various former times. In addition to

the above-mentioned vertebrate fossils, the writer has gathered many of lesser perfection

or importance, as well as everything that came in his way illustrative of the life of

former geologic times. The beds of Kansas have proved to be rich territory and to possess

material of very great scientific interest, as is evidenced by the desire of the various

museums mentioned above to secure fine illustrative examples of this ancient Kansas fauna.

The discovery and collection of these has been a

constant source of joy and pleasure, entirely aside from any financial value they hold. On

the other hand, it has been a very great disappointment that these things, of such great

scientific interest, had to leave the state. Instead of finding a natural home at the

University, the museums of the capital, or with the educational institutions of the state,

they are scattered in other states, or even across the sea. Moreover, the finding of each

new and valuable specimen reduces the probability of finding more in the years to come.

The writer has tried to bring to a successful issue several movements through which the

results of his collecting expeditions in Kansas would remain within the boundaries of the

state - within the district where the huge and strange forms lived their lives. To his

regret he has so far failed.

|