Credits: I am grateful to Carl Mehling of the American Museum of

Natural History for supplying me with a copy of this article. Popular Science News (not to

confused with Popular Science Monthly) was a short lived journal and is rarely found in

libraries.

Suggested references:

Case, E. C. 1897. On the osteology and relationships of Protostega.

Journal of Morphology 14: 21-55, with pls. iv.

Cope, E. D., 1872a. [Sketch of an expedition in the valley of the

Smoky Hill River in Kansas]. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society

12(87):174-176. (meeting of October 20, 1871)

Cope, E. D., 1872c. A description of the genus Protostega, a

form of extinct Testudinata. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society

12(88):422-433. (March 1, 1872)

Cope, E. D., 1872d. On the geology and paleontology of the Cretaceous

strata of Kansas. Annual Report of the U. S. Geological Survey of the Territories

5:318-349 (Report for 1871).

Cope, E. D., 1875. The Vertebrata of the Cretaceous formations of the

West. Report, U. S. Geological Survey Territories (Hayden). 2:302 p, 57 pls.

Hay, O. P., 1895. On certain portions of the skeleton of Protostega

gigas. Publ. Field Columbian Museum, Zoological Ser. (later Fieldiana: Zoology),

1(2):57-62, pls. 4 & 5.

Hay, O. P. 1908. The fossil turtles of North America. Carnegie

Institution of Washington, Publication No. 75, 568 pp, 113 pl.

Hooks, G. E., III. 1998. Systematic revision of the Protostegidae,

with a redescription of Carcarichelys gemma Zangerl, 1957. Journal of Vertebrate

Paleontology, 18(1):85-98.

Lane, H. H., 1946, A survey of the fossil vertebrates of Kansas, Part

III, The Reptiles, Kansas Academy Science, Transactions 49(3):289-332, 7 figs.

Shimada, K., M. J. Everhart, and G. E. Hooks, 2002. Ichthyodectid

fish and protostegid turtle bitten by the Late Cretaceous lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina

mantelli. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22(suppl. to 3):106A. (Abstract)

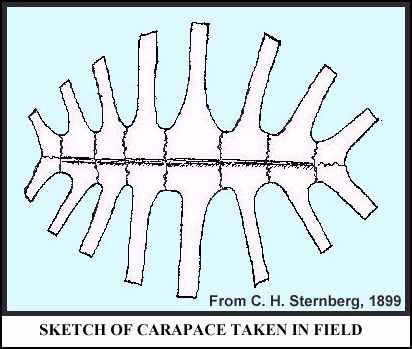

Sternberg, C. H. 1899. The

first great roof. Popular Science News 33:126-127, 1 fig.

Sternberg,

C. H. 1900. Fossil collector's experiences. Popular Science

News 34:34.

Sternberg,

C. H. 1900. The sharks of Kansas. Popular Science News

34:38.

Sternberg, C. H. 1905. Protostega gigas and other Cretaceous reptiles and

fishes from the Kansas chalk. Kansas Academy Science, Transactions 19:123-128.

Sternberg, C.H., 1906. Some animals discovered in the fossil

beds of Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 20:122-124.

Sternberg, C.H. 1907. My expedition to the Kansas Chalk for

1907. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 21:111-114.

Sternberg, C.H. 1909. The life of a fossil hunter. Henry

Holt and Company, 286 p. (reprinted by the Indiana University Press, 1990).

Wieland, G.R. 1896. Archelon ischyros: a new gigantic

cryptodire testudinate from the Fort Pierre Cretaceous of South Dakota. American Journal

of Science, 4th Series 2(12):399-412, pl. v.

Wieland, G.R. 1902. Notes on the Cretaceous turtles, Toxochelys

and Archelon, with a classification of the marine Testudinata. American

Journal of Science, Series 4, 14:95-108, 2 text-figs.

Wieland, G.R. 1906. The osteology of Protostega, Memoirs of

the Carnegie Museum, 2(7):279-305.

Wieland, G.R. 1909. Revision of the Protostegidae.

American Journal of Science, Series 4. 27(158):101-130, pls. ii-iv, 12 text-figs.

Williston, S.W. 1898. Turtles. The University Geological

Survey of Kansas, Part VI. 4:349-369. pls. 73-78.

Williston, S.W. 1902. On the hind limb of Protostega. American Journal of

Science, Series 4, 13(76):276-278, 1 fig.

Williston, S.W. 1914. Water reptiles of the past and present. Chicago University

Press. 251 pp. (Free,

downloadable .pdf version here)