Charles H. Sternberg

1898.

Ancient monsters of Kansas.

Popular Science News 32:268.

|

Charles H. Sternberg 1898. Ancient monsters of Kansas. Popular Science News 32:268. Copyright © 2004-2010 by Mike EverhartePage created 11/09/2004; Last updated 12/22/2010 |

Wherein Charles H. Sternberg describes some of the strange creatures that lived in the oceans covering Kansas during the Late Cretaceous.

See more about Charles H. Sternberg here.

| 268 POPULAR SCIENCE NEWS DECEMBER, 1898 |

| ANCIENT MONSTERS OF KANSAS.

BY CHARLES H. STERNBERG. There is no country on earth better known to the student of ancient life than that extending from western Trego county, Kansas, to the Colorado line, including the brooks and ravines of the Smoky Hill river and its forks, for here are the burial grounds of a race of reptiles, fishes, birds and winged lizards, that lived long ago. Long before the Rocky mountains were uplifted, a vast sea—the Cretaceous—covered the region west of the limestone rocks of eastern Kansas. These rocks the upper Carboniferous — were the eastern shore line of this great ocean, which at first was covered with islands on which grew luxurious forests of fig, magnolia, sassafras, redwood, birch, etc. of which over 400 species then flourished. The sediment laid down by the rivers that flowed into it and covered the ocean floor, was composed of sand and clay, and the exposures in Ellsworth and other counties of central Kansas, are differently colored sandstones and clays. This group of the Cretaceous was named the Dakota, or Cretaceous No. 1 by the United States geologist Dr. F. V. Hayden, who named the succeeding ones. Later the sea deepened and beds of compact limestone, composed of the ground-up fragments of clam-like shells and black shale beds were laid down. The stone posts of Kansas come from this formation, which is known as the Ft. Benton group or the Cretaceous No. 2. It was first studied by Hayden at Ft. Benton, Montana. On top of this lie the blue shale, yellow and reddish chalks of the Niobrara, while on the heads of the north and south forks of the Smoky are the black shales of the Ft. Pierre group or Cretaceous No. 4. All these groups contain fossil remains, but the Niobrara is by far the richest. My brother, Dr. Geo. M. Sternberg, U. S A., made one of the first collections in this region, while surgeon of a scouting party who went from Ft. Harker in Ellsworth County to Ft. Wallace, following the old Butterfield stage route up the Smoky river. In 1872 the late Prof. Cope, of Philadelphia, conducted an expedition here, and both he and Prof. Marsh, of Yale College, kept parties in this field every year until about 1878. There has hardly been a year since that collectors have not been at work searching for monsters that prove that “truth is stranger than fiction.” The large universities of the world have specimens from these famous beds. How shall I give even a slight idea of these wonderful birds, reptiles, pterodactyls, fishes and shells? Shall we in imagination walk along the shores of that grand ocean, explore its bays and estuaries, and replace the flesh on the bony skeletons, that only remain to teach us of their power when full of life and motion?

We climb a ridge, and a shout of surprise involuntary

arises from our lips as we find the waters replete with strange animals, and the sun above

us darkened by the wings of great flying dragons, who flap their leathery pinions over the

bay, or with broad expanded wings, 20 feet from tip to tip, rest motionless upon the air.

Their heads 4 ft. in length, terminate in long bony toothless beaks; their large powerful

eyes are watching the depth below; a luckless fish attracts the monster’s attention

and with fearful speed he dashes into the blue water and reappears with the poor fish

which rapidly disappears down his cavernous throat; then he resumes his majestic circles

and watches for another victim. |

This wonderful pterodactyl or flying

lizard had the bones of the first finger elongated. In the museum of the Kansas State

University is mounted an arm and elongated finger stretched out over 9 ft in length. Their

bones were all strong and hollow and must have been extremely light. Their leathery wings

were attached to the elongated fingers and hinder limbs, whose powerful claws enabled them

to seek rest suspended by them from a friendly cliff.

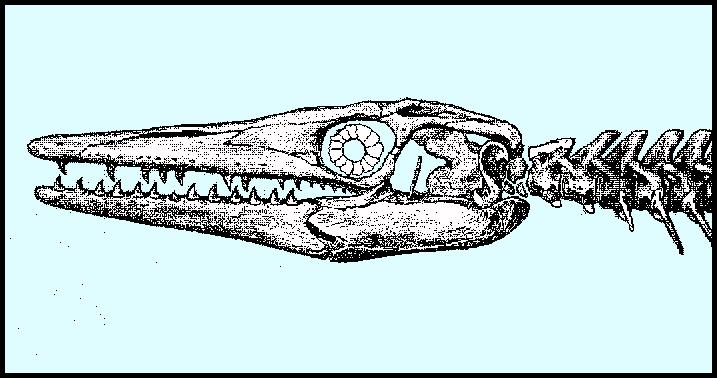

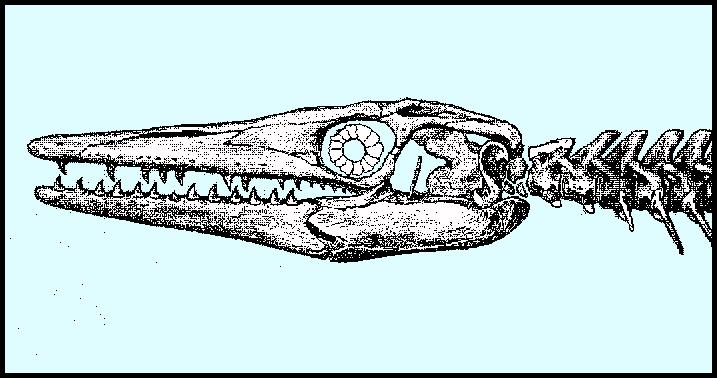

But see! far in the distance the water lashed, the white foam surging off from either side

of a pathway made by an approaching reptile of mammoth proportions, and just in front of

us we see the cause, for a mighty sea serpent, (or saurian as they are called) lifts

itself half way out of the water which drips from its scale covered and brilliantly

colored body. We are near enough to see the look of defiance in the large eyes that are

set well back in the long conical bead.

A long snake-like body follows, covered with scales about the size and shape of those of a Kansas bull

snake. The pair of hind paddles are smaller, and stretched nut behind is the flexible

tail, a cross section of which would be diamond shaped. This, with the paddles, is used as

a propeller and a rudder as well. But the adversary approaches, and our near-by saurian

coils his belligerent tongue, drops in the water with a splash, puts his powerful muscles

of motion at work and accepts the challenge for battle. |

Suggested references:

Cope, E. D. 1871. On the fossil reptiles and fishes of the Cretaceous rocks of Kansas. Art. 6, pp. 385-424 (no figs.) of Pt. 4, Special Reports, 4th Ann. Rpt., U.S. Geological Survey Territories (Hayden), 511 p.

Cope, E. D. 1872. Note of some Cretaceous vertebrata in the State Agricultural College of Kansas. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 12(87):168-170. (for Oct. 20, 1871 meeting)

Cope, E. D. 1872. Sketch of an expedition in the valley of the Smoky Hill River in Kansas. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 12(87):174-176. (for Oct. 20, 1871 meeting)

Rogers, Katherine. 1991. A dinosaur dynasty: The Sternberg Fossil Hunters, Mountain Press Publishing Company, 288 pages.

Sternberg, C. H. 1884. Directions for collecting vertebrate fossils. Kansas City Review of Science and Industry 8(4):219-221.

Sternberg,

C. H. 1898. Ancient monsters of Kansas. Popular Science

News 32:268.

Sternberg, C. H. 1899. The first great roof. Popular Science News 33:126-127, 1 fig.

Sternberg,

C. H. 1899. A Kansas mosasaur. Popular Science News

33:259-260.

Sternberg,

C. H. 1900. Fossil collector's experiences. Popular Science

News 34:34.

Sternberg,

C. H. 1900. The sharks of Kansas. Popular Science News

34:38.

Sternberg, C. H. 1905. Protostega gigas and other Cretaceous reptiles and fishes from the Kansas chalk. Kansas Academy Science, Transactions 19:123-128.

Sternberg, C. H., 1906. Some animals discovered in the fossil beds of Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 20:122-124.

Sternberg, C. H. 1907. My expedition to the Kansas Chalk for 1907. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 21:111-114.

Sternberg, C. H. 1909. An armored dinosaur from the Kansas chalk. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 22: 257-258.

Sternberg, C. H. 1911. In the Niobrara and Laramie Cretaceous. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 23:70-74.

Sternberg, C. H. 1913. Expeditions to the Miocene of Wyoming and the chalk beds of Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 25:45-49. (Papers - Forty-fifth annual meeting, 1912) State Printing Office, Topeka.

Sternberg, C. H. 1922. Explorations of the Permian of Texas and the chalk of Kansas. 1918. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 30(1):119-120.

Sternberg, C. H. 1922. Field work in Kansas and Texas. {1919] Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 30(2):339-348. (Papers - Fifty-second annual meeting, 1920), State Printer, Topeka.