|

Just About Mosasaurs

Copyright © 1996-2011 by Mike Everhart

Last revised 03/04/2011

Left: Tylosaurus

proriger, a large marine reptile from the Western Interior Sea during the Late

Cretaceous from about 90 to 65 million years ago). Modified

after an illustration by Gregory S. Paul. |

MOSASAURS - LAST OF THE GREAT

MARINE REPTILES - Article in Prehistoric Times

First and most importantly, mosasaurs are not dinosaurs. They

are extinct marine reptiles that are believed to be distantly related to monitor lizards

such as the Komodo Dragon. Based on recent

evidence, however, it may be that they were even more closely related to snakes than monitor lizards. The discovery and study of

mosasaurs near Maastricht in Europe in the late 1700s predated the finding of dinosaurs by

more than fifty years. Many complete mosasaur specimens have been found in the Smoky

Hill Chalk Member of the Niobrara Formation of Western Kansas, and some of the first

mosasaur remains were collected by Professor Benjamin

Mudge and Dr. George M. Sternberg more than 130

years ago. A few years later, in a series of scientific expeditions sponsored by O.

C. Marsh and Yale University, hundreds of specimens were collected. As a group, the

fossilized remains of mosasaurs had been found all over the world, from Kansas to South

Dakota to North Dakota to Montana to New Mexico to Colorado to Texas to

Arkansas to Tennessee to Georgia to Alabama to New Jersey to California, to Canada,

from the Netherlands to Sweden, from Turkey to Israel to Africa, and from Brazil

to Peru to Australia and New Zealand to the islands off the coast of

Antarctica.

Since 1998, Jim Martin, a paleontologist from the South Dakota School of

Mines and Technology has collected several partial sets of

mosasaur remains from Vega Island off the eastern side of the Antarctic Peninsula.

According to Martin, the specimens included several juveniles which are very rare in the

fossil record. A new species of tylosaurine mosasaur was described from the same

area by Fernando Novas and others in 2002.

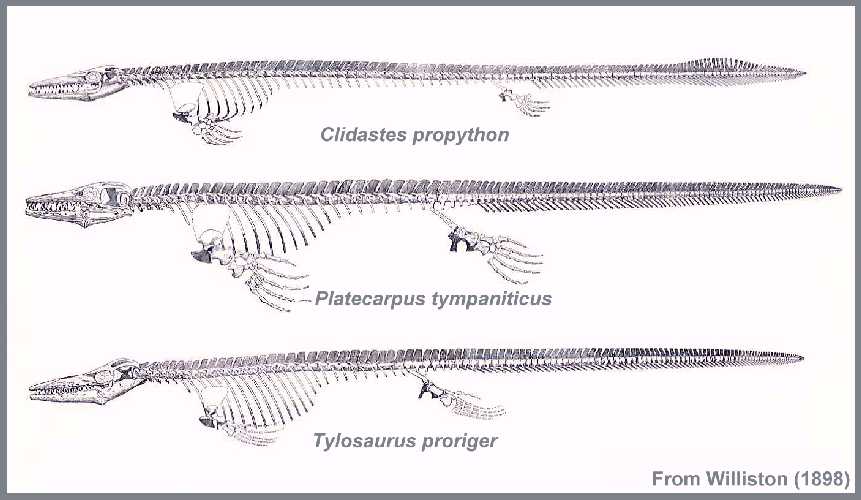

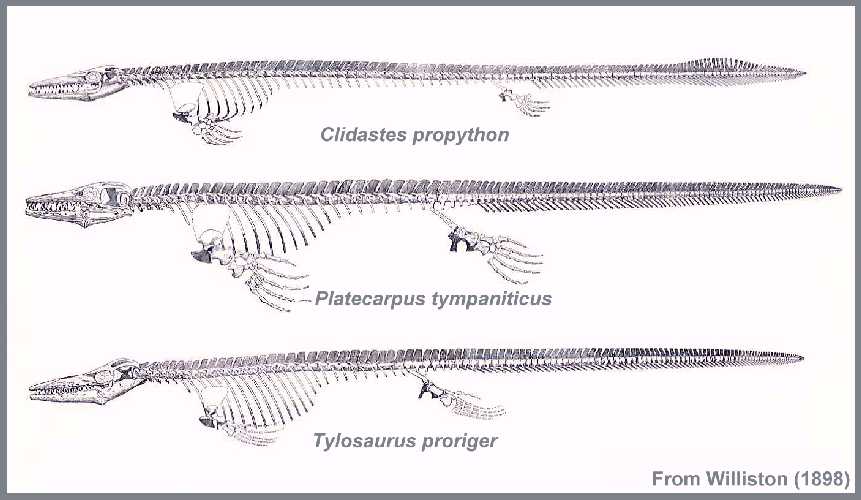

Shown below is a drawing from Williston (1898) that shows the skeletons of

three common species of mosasaurs from Kansas; Clidastes

propython, Platecarpus tympaniticus and Tylosaurus proriger. Although these three species are

shown about the same size in the drawing, in life, Clidastes was the smallest

(about 12-15 feet); Platecarpus was the next largest (about 24 feet) and Tylosaurus

was the largest (30 plus feet):

New data on the skull and size of

Tylosaurus nepaeolicus

A revised biostratigraphy of

mosasaurs in the Smoky Hill Chalk of Western Kansas

Mosasaurs: Last of the Great Marine

Reptiles

CLICK HERE TO

VISIT THE OCEANS OF KANSAS "VIRTUAL MOSASAUR MUSEUM"

Click here for some excellent

drawings of mosasaur skulls from Williston (1898)

Click here for the dig of an early Tylosaurus

proriger (Kansas)

Click here for the dig of a Platecarpus

tympaniticus (Kansas)

Click here for the dig of a Clidastes

liodontus (Kansas)

Click here for the dig of a Platecarpus

planifrons(?) (Kansas)

Click here for the dig of a rare Globidens

(shell crushing) mosasaur (Kansas)

Click here for pictures of one of

the largest mounted mosasaur specimens in the world (Kansas)

Click here for pictures of a very

large Plioplatecarpus from North Dakota

Click here for the dig of a Mosasaurus

conodon from South Dakota

The word "mosasaur" literally means "Meuse Reptile", and

was so named because the first remains of a mosasaur to be discovered were found close

to the Meuse River, near the

town of Maastricht in the Netherlands, inside an underground limestone mine sometime

between 1770 and 1774. Eventually, this specimen was given the name Mosasaurus

hoffmanni in honor of Dr. C. K. Hoffman who had studied the remains and believed them

to be those of a giant crocodile. For those who are interested in the early history

of paleontology, the battle for possession of this specimen is a very unusual story, which includes being confiscated by the

French army in 1795 in exchange for several cases of wine. The specimen is still in the

French national museum in Paris, so the story continues even today.

In 1845, a German naturalist by the name of Dr. George August Goldfuss published a paper describing a mosasaur from the wilds of North America (in what was to

become South Dakota). The specimen (Mosasaurus Maximiliana) had been

acquired by Prince

Maximilian zu Wied during his visit to North America in the 1830s and is in the

Goldfuss collection of the natural history museum at the University of Bonn, Bonn,

Germany.

For more information about the origin and meaning of

mosasaur names, go to Ben Creisler's Mosasauridae Translation and

Pronunciation Guide, a recent addition to the The Dinosauria On-Line Dinosaur

Omnipedia.

|

Many millions of years ago, probably during the early part of the

Cretaceous Period, the ancestors of mosasaurs left the land and began to adapt to the

marine environment in much the same manner that the ancestors of modern whales returned to

the sea. Like whales, mosasaurs also had to surface periodically to breathe.

Instead of an "up and down" movement their tail like whales and porpoises,

however, mosasaurs used a sinuous, undulating movement of their tails to propel themselves

rapidly through the water. This movement would have been much like that of a swimming

alligator or snake. Check out this excellent, technical paper by Richard Cowen if

you would like more information about the Locomotion and Respiration

in Marine Air Breathing Vertebrates. This picture of a

re-constructed Mosasaurus skull was adapted from a photograph provided by

Greg Livaudais. |

By the time of the deposition of the Smoky Hill Chalk (beginning about 87 mya),

mosasaurs were quickly becoming the dominant carnivores in many

marine environments around the world, feeding on fish, squid, ammonites, turtles,

small plesiosaurs, and even other mosasaurs. Although some other reptiles, including plesiosaurs (and Kronosaurus),

and marine crocodiles like Deinosuchus, were as large and certainly as dangerous,

none were as successful in terms of numbers, or as wide spread as the mosasaurs. Another

kind of marine reptile, the Ichthyosaurs , were

almost extinct by the time the mosasaurs were evolving. This diverse and highly

specialized group had ruled the oceans for millions of years during the Triassic and

Jurassic periods, but became extinct well before the end of the Cretaceous. The

remains of some of the largest Ichthyosaurs known (Shonisaurus

popularis) were found in the western United States (Nevada). It is very

possible that mosasaurs were so successful because they were able to move into the

ecological niches left vacant by the extinction of the Ichthyosaurs.

Like the Ichthyosaurs,

mosasaurs gave live birth to their young and may

have even provided them some form of parental protection. Evidence exists that

mosasaurs of all sizes and age groups were living in mid-ocean during the deposition of

the Smoky Hill Chalk in the Western Interior Seaway.

The Cretaceous ocean must have been a very hostile environment for all

creatures. Mosasaurs shared the ocean with giant turtles like Protostega, huge fish like Xiphactinus, a creature that grew to a length of more than 18

feet and had three inch long teeth. There were giant sharks

like Cretoxyrhina mantelli, that cruised the shallow

waters of the Inland Sea and may have grown to as large as 22 feet in length. These sharks

looked much like (but were not closely related to) the Great White Shark in the movie, Jaws.

Swarms of smaller sharks called Squalicorax

scavenged carcasses of dead animals, and may have preyed on the sick and injured.

The air above the ocean was also filled with threats to small creatures on or

near the surface. Giant Pteranodons, flying

reptiles with wingspreads of more than 20 feet and mouths that gapped open more than three

feet, were always on the prowl for food for themselves and their young. Since the remains

of these Pteranodons are found in the middle of the seaway, hundreds of miles

from the nearest shore, these large flying reptiles must have been able to soar over the

ocean for hours or days at a time, much like a modern albatross. There was even a six foot

tall, flightless sea bird, called Hesperornis regalis,

that swam in the Late Cretaceous seas and dived to catch fish much like a modern penguin.

We know that it was carnivorous because its jaws were still equipped with many sharp

teeth. It must have preyed on whatever smaller animals that it could catch. Smaller birds,

like Ichthyornis, would have looked and acted

much like the seagulls and terns of today. Even these small sea birds had sharp teeth in

their jaws.

|

Mosasaurs preyed on smaller

individuals of other species, including ammonites, fish,

birds and even smaller mosasaurs. One genus, called Tylosaurus,

reached lengths of 30 to 40 feet in the Western Interior Sea during the deposition of the

chalk . By the Late Cretaceous, just before the end of the Age of Dinosaurs 65 million

years ago, mosasaurs were becoming larger and more specialized. Some kinds of

mosasaurs such as Mosasaurus and Hainosaurus,

were as large as 45-50 feet in length while others, like Globidens,

had developed specialized, ball shaped teeth for crushing clams or other hard shelled

invertebrates. All things considered, it was not a very safe or friendly place to

live. Mosasaurs were at the top of the food chain, but

life could be very short for the unwary. Fortunately for

humankind, the mosasaurs also became extinct along with

the dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous Period. They are not something you would want

to share your oceans with. |

Click here to read about "Mosasaurs: Last of the

great marine reptiles"

Click here to visit the Oceans of Kansas Paleontology

Virtual Mosasaur Museum

Click here for some excellent drawings of mosasaur

skulls from Williston (1898)

Click here for a list of references in my library about

mosasaurs and plesiosaurs.

Click here for

more information about the meaning and origin of mosasaur names in Ben Creisler's

Translation and Pronunciation Guide